This pathway complements NNLM’s resources on rural health by exploring evaluation considerations for programs that seek to improve health outcomes for individuals in rural communities.

Rural settings can be defined in many ways, but perhaps most simply by stating that it is any population, housing, or territory not located in urban areas. In 2010, the US Census found that 19% of the population, or almost 60 million people, live in rural areas.

Working on a project with a small award (less than $10,000)? Use the Small Awards Evaluation Toolkit and Evaluation Worksheets to assist you in determining key components for your evaluation!

When developing an evaluation, consider the context of your program. The context can change how your evaluation is designed and implemented since different settings and populations have different needs and abilities to participate in evaluations.

- Evaluate what level of access participants have to health services and health information. The low-density populations of rural areas, combined with long distances to reach health services and providers, mean that residents in rural areas are more predisposed to issues with access compared to their urban counterparts.

- Review multiple dimensions of access. Access includes not only whether the service or information is available or not, but also the ability to utilize the service. Finances and health insurance status, as well as transportation, broadband and internet access, and language barriers can all play a part in access.

- When developing a sampling strategy, remember that issues with access may result in sampling some participant groups more than others. If you are seeking information that could be applied to the community as a whole, remember that you will have to sample the entire community, and not just those who have access to the program.

| Barriers to Access | |

|---|---|

| Barrier | Definition & Examples |

| Structural | The number, type, concentration, location, and organizational configuration of providers (often predicated by the health care financing system)

|

| Financial | The cost of care to individuals and families, including the presence and type of health insurance coverage (includes consideration of those who are underinsured)

|

| Personal & Cultural | A set of either explicit or implicit rules that determine the behavior of social subjects in relation to their health

|

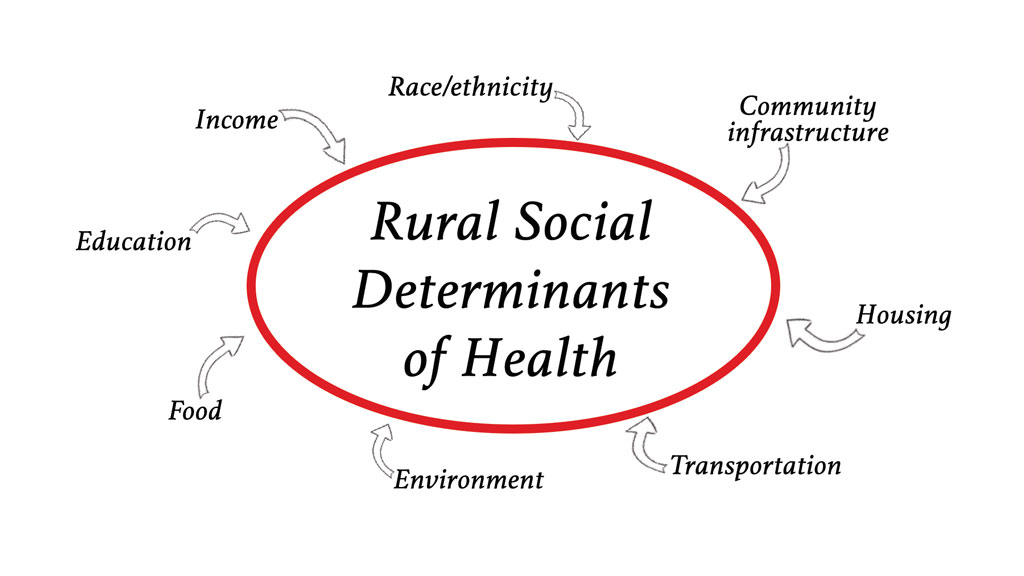

- Gather information on social determinants of health. The National Advisory Committee on Rural Health and Human Services advises that in order to improve health and quality of life in rural areas, policy makers should consider the social determinants of health of geography; wealth, income and poverty; education and labor markets; and transportation.

- Consider how health disparities change who and how participants engage in the program. Health disparities are evident in rural populations, because of the complex systemic issues related to the social determinants of health. For example, from 1999-2014, the rates of death of all five leading causes of death in the United States were higher in rural areas than in urban areas.

- Analyze data on health disparities and social determinants of health separately for each geographic location. When evaluating across multiple geographic areas, remember that social determinants of health and health disparities may be different for each area. Some areas, such as Appalachia, the US-Mexico Border, and American Indian and Alaska Native communities, have larger health disparities than other rural areas.

- Present health disparities from an equity lens. Health disparities are the result of complex systemic and structural inequities, rather than qualities inherent to a group of individuals. When examining and communicating health disparities through a lens of equity, one should recognize the issues leading to the disparities, including the social determinants of health.

Health Literacy

- Consider how health literacy levels change your program. A higher proportion of residents of rural areas have lower health literacy than urban areas, which can be explained by differences in age, gender, race, ethnicity, education and income between rural and urban populations.

- Measure health literacy at the start of the program. Health literacy has been shown to change the success of programs and should be measured at the start of the program to see if it could affect program outcomes.

Step 1

Step 1: Do a Community Assessment

The first step in designing your evaluation is a community assessment. The community assessment phase is completed in three segments:

- Get organized

- Gather information

- Assemble, interpret, and act on your findings

- This phase includes outreach, background research, networking, reflecting on the evaluation and program goals, and formulating evaluation questions.

- Conduct a stakeholder analysis to identify individuals or groups who are particularly proactive or involved in the community. Find out why they are involved, what is going well in their community, and what they would like to see improved.

- In rural health settings, participatory evaluation methods can help to improve the relevance and visibility of the community assessment.

Positive Deviance

- Consider identifying early adopters among rural health stakeholders. When creating a community assessment, consider the questions that could be asked to help identify these individuals and their role in the community.

- Use the Positive Deviance (PD) approach to identify these early adopters.

- Please note this process is time and labor intensive and requires a skilled facilitator comfortable with ambiguity and uncertainty. This process may not be feasible within the time constraints of the typical NNLM-funded project.

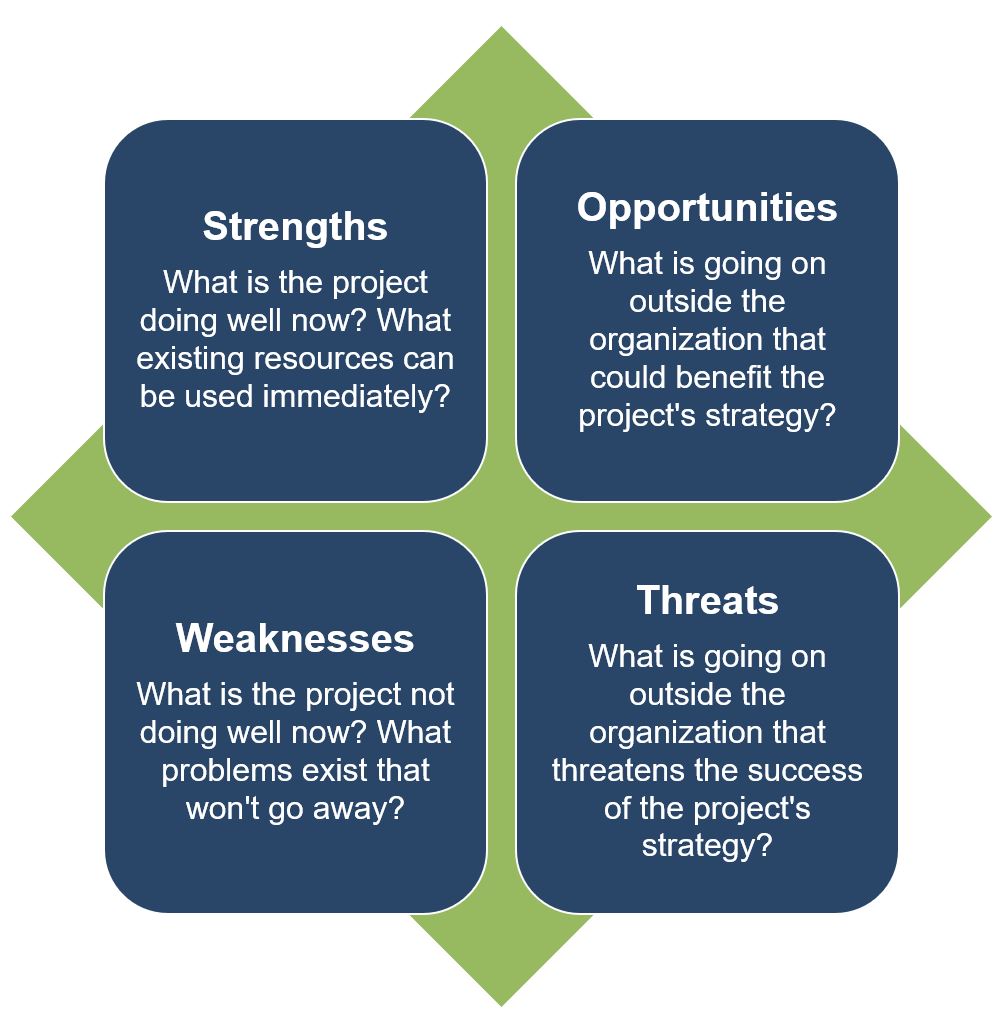

SWOT Analysis

- As part of the rural health stakeholder analysis, conduct a SWOT Analysis for the program to identify what you and your team already know.

- A SWOT analysis is typically used to assess an organization or program's internal strengths and weaknesses and the opportunities and threats to the organization or program in the external target community.

- To apply this tool in health information outreach project planning, we suggest that you gather your team of advisors to identify what you know about the project team's internal strengths and weaknesses for working with a specific community and the strengths and barriers in the community to providing health information outreach.

- More information on SWOT Analysis

- Example Rural Health SWOT Analysis

- This phase includes gathering data from different external and internal sources to inform the development of your program and evaluation plan.

- Gathering information in rural settings can involve a wide variety of techniques and tools, from individual interviews, site visits, group discussions, surveys, and synthesis of existing sources of information.

- County and state health departments, local reporting agencies, and libraries may have data available for your use.

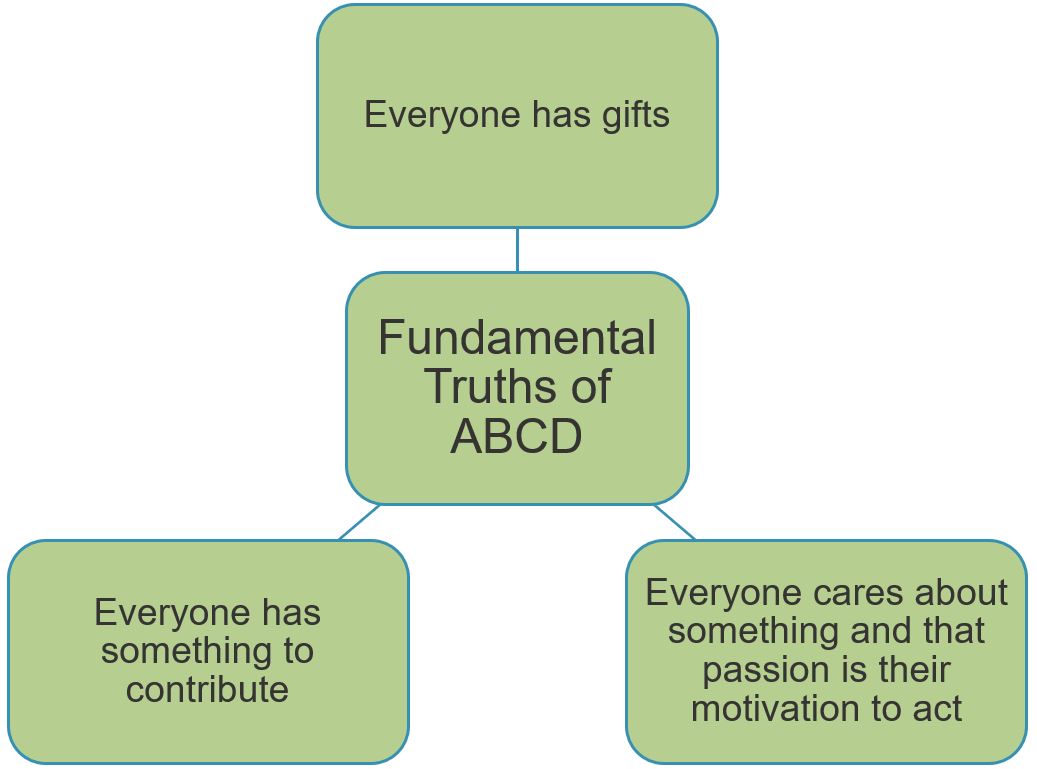

Asset Based Community Development (ABCD) Mapping

- Asset-based community development (ABCD) mapping approaches can be used to assess the resources available in a community and focus on participatory involvement of community members and organizations.

- In general, asset mapping is used to identify individual and community gifts and assets, stimulate discussion and planning, and connect individual community members.

- Guidance and resources on ABCD are available through the Asset Based Community Development Institute.

| Types of Asset Mapping | |

|---|---|

| Type | What is identified |

| Individual Asset Inventories | Gifts, talents, dreams, hopes, fears |

| Association Mapping |

|

| Institutional Mapping |

|

| Physical Space Mapping |

|

| Neighborhood Economy Mapping |

|

Existing Data Sources

- Existing data, where available, can be a helpful resource for developing your evaluation plan.

- The following data sources CANNOT be used to report against program outcomes, but they may be helpful during a needs assessment or program design phase in understanding the context in which the program will be placed:

- Rural Health Information Hub’s Data Sources & Tools Relevant to Rural Health

- The American Community Survey (ACS)

- An annual survey of communities, that collects economic and social data. It collects some information at the sub-county level.

- The County Health Rankings

- Provides an easy-to-understand health profile of counties in the United States.

- Economic Research Services (ERS) State Fact Sheets

- Compiles economic and demographic information from different sources into fact sheets.

- They provide rural-specific information, useful to rural health pathways.

- Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project

- Provides hospital health information at county and sub-county levels.

- There are a variety of already created tables, but there is the option to make your own table based on information needs.

- U.S. Census QuickFacts

- Displays US census information in easy to understand tables.

- Rural Data Portal

- Easy-to-use web portal that can be used to examine information at the national, state, and county level on a variety of demographic, social, economic, housing and finance data.

- This phase includes processing the information gathered into understandable takeaways that can be used for the program and the evaluation.

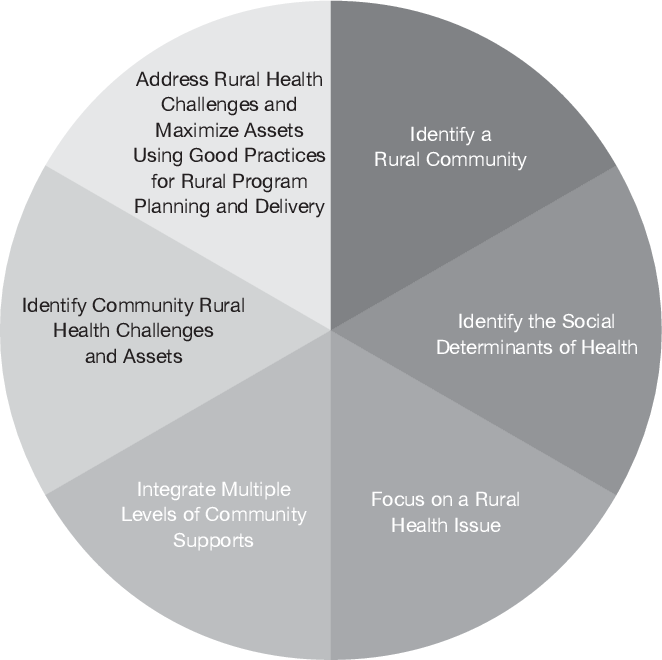

Rural Health Framework

- Deanna White developed a framework for rural health population programming planning and delivery. She emphasizes throughout the article the importance of gathering evidence to clarify and define the program.

- Your community assessment can help to inform the different dimensions of the framework.

Step 2

Step 2: Make a Logic Model

The second step in designing your evaluation is to make a logic model. The logic model is a helpful tool for planning a program, implementing a program, monitoring the progress of a program, and evaluating the success of a program.

Make a Logic Model

- Consider how the program's logic model will assist in determining what is, or is not, working in the program's design to achieve the desired results.

- Since access can change how rural populations interact with programs, consider how to include program growth and reach in your logic model. Including logical steps on how the program reaches the right people, at the right time can help clarify program coverage.

- Be open to new and alternative patterns in your logic model. Have stakeholders and community members review your logic model, paying particular care to how change occurs across the logic model. Listen to voices who can say whether the strategies are beneficial, and whether strategies could be successful.

- More information on Logic Models

- Example Rural Health Logic Model

Tearless Logic Model

- To facilitate the creation of the logic model, community-based organizations can consider using the Tearless Logic Model process.

- The Tearless Logic Model uses a series of questions to assist non-evaluators in completing the components of the logic model. Questions used in the Tearless Logic Model

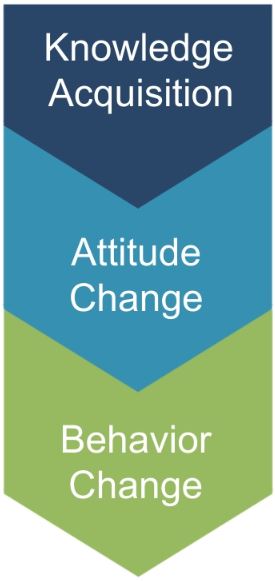

Knowledge, Attitudes, & Behaviors

- Programming should consider improvement in the knowledge-attitude-behavior continuum among program participants as a measure of success. The process of influencing health behavior through information, followed by attitude changes and subsequent behavior change, should be documented in the logic model.

- Focusing on behavior change is more likely to require Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval.

- Cultural humility can help us better understand the communities we are working with by framing our evaluation in ways that meet the needs of the community.

- Knowledge Acquisition:

- What is the program trying to teach or show program participants?

- What understanding would a program participant gain over the course of the program? Often knowledge acquisition occurs as a short-term outcome of the program.

- Be sure to examine not only what is learned, but where, when, and how program participants will learn it.

- In rural settings, it is important to consider how individuals will gain knowledge, as the distances from residences, health literacy levels, and social determinants of health can often hinder knowledge acquisition.

- It is important to consider the starting level of health literacy as this can affect more the downstream outcomes (attitude and behavior change).

- Attitude Change:

- What mindsets or beliefs are the program seeking to build or change? Be sure to consider cultural differences in attitudes in the community you are working with.

- Are there misconceptions about the topic or health information, and does that belief change after the program has been implemented?

- To what extent do participants agree or disagree with statements related to the program?

- Behavior Change:

- Are the actions of program participants different than what would have been expected without the program?

- Health information outreach programs will likely focus on changing information seeking practices, rather than health practices.

- In rural health settings, behavior change information may be captured in reports from health facilities or may be already collected by government or non-government agencies.

- When examining previously collected data, consider whether it was collected from the same target population as the program you are evaluating, and over the same time frame as the program.

- Note that most NNLM projects focus on the dissemination of health information/health education and often do not take place over a long enough period of time to observe behavior change.

- As such, examining/measuring behavior change may be out of the scope of the NNLM-funded project unless the projects runs for multiple cycles over an extended period of time.

Step 3

Step 3: Develop Indicators for Your Logic Model

The third step in designing your evaluation is to select measurable indicators for outcomes in your logic model.

Measurable Indicators

- Consider whether your outcomes are short-term, intermediate, or long-term

- Most NNLM projects are of short duration and should focus only on short-term or intermediate outcomes.

- It may be necessary to use more than one indicator to cover all elements of a single outcome.

- If possible, use multiple indicators to measure important outcomes.

- How to develop measurable indicators

- Example Rural Health Measurable Indicators

Healthy People 2030

- Healthy People 2030 Leading Health Indicators are a set of 23 priority indicators designed to drive progress in health and wellbeing across the lifespan in the United States.

- The Leading Health indicators can be reviewed for relevance to your rural health program logic model.

Social & Behavior Change Communication

| Example Indicator |

| Percent of respondents who report that the messages are culturally sensitive and relevant |

| Number of individuals reached by messages |

| Percent of intended audience who were reached by messages |

| Percent of audience reporting exposure to messages (can specify the source: radio, television, electronic platforms, or print) |

| Percent of audience who recall hearing or seeing a specific product, practice, or service |

| Percent of audience who can recall specific promoted information in a correct manner |

| Percent of audience with a favorable (or unfavorable) attitude toward the product, practice, or service |

| Percent of audience who perceive risk (or benefits) in a given behavior |

| Percent of audience who believe that the recommended practice/ product will change their risks (or benefits) |

| Percent of audience who intend to adopt a certain product, practice, or service in the future |

| Percent of audience who practice a recommended behavior |

| Percent of audience who use a service or product |

Demographic Data

- Collect data on demographics as part of your survey process. It is important to understand your participants' backgrounds and how that may affect their engagement with your program.

- During analysis, compare differences in backgrounds against outcome results. If there are gaps identified in reaching certain populations, consider adjustments to program implementation to serve all participants equitably.

- More information on collecting demographic data

Step 4

Step 4: Create an Evaluation Plan

The fourth step in designing your evaluation is to create the evaluation plan. This includes:

- Defining evaluation questions

- Developing the evaluation design

- Conducting an ethical review

- Evaluation questions help define what to measure and provide clarity and direction to the project.

- Process questions relate to the implementation of the program and ask questions about the input, activities, and outputs columns of the logic model.

- The complexities of implementing programs in rural health settings can place importance on process questions.

- Outcome questions relate to the effects of the program and relate to the short, intermediate, and long-term columns of the logic model.

- Evaluation design influences the validity of the results.

- Most NNLM grant projects will use a non-experimental or quasi-experimental design.

- Quasi-experimental evaluations include surveys of a comparison group - individuals not participating in the program but with similar characteristics to the participants - to isolate the impact of the program from other external factors that may change attitudes or behaviors.

- Non-experimental evaluations only survey program participants.

- If comparison groups are part of your quasi-experimental design, use a 'do no harm' approach that makes the program available to those in the comparison group after the evaluation period has ended.

- If you chose to compare outcomes of program participants to non-program participants, it may be helpful to examine other geographic areas that are like the rural area your program is located in.

- Check to see if the density of the population, the size of the population, and social determinants of health are like those where your program is operating.

- More information on Evaluation Design

Indigenous Evaluation

- Indigenous evaluation is useful to understand and use when you are evaluating a program working with indigenous or Native-American groups.

- Indigenous evaluation is rooted in indigenous ways of knowing, interacting with others, and utilizes indigenous frameworks and cultural paradigms.

- Different tribal communities have different cultures, and an approach that matches one context may not work in another. The community assessment can be helpful for determining if your approach meets the needs of the tribal community you are working with.

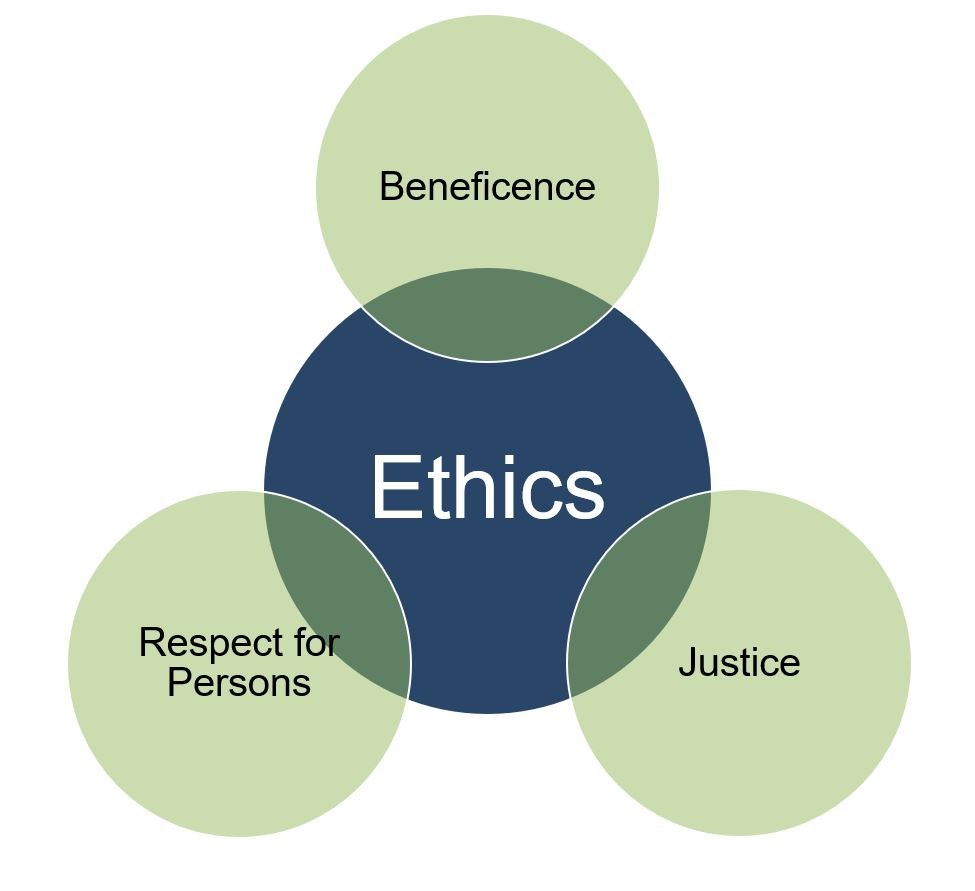

Ethical Considerations

Consider the Belmont Report principles to examine rural health population ethical considerations:

- Respect for Persons:

- It is important to consider if a health condition would change a participant’s ability to participate or opt out of the evaluation.

- The primary language of a program participant can change whether they understand what is required of them for the evaluation. Translated versions of informed consent and data collection tools may need to be used.

- Beneficence

- If individuals have limited access to resources, it can affect how and if a participant engages with the benefits the evaluation and program provides. If an individual has limited resources, you can increase the benefits they receive through monetary compensation or gifts.

- In the process of completing the evaluation, consider if you are asking your participants to do things or use resources that they might not have easy access to.

- Justice

- In rural settings, it may be harder for some groups to receive benefits than others.

- Consider how your evaluation would exacerbate or improve the distribution of benefits.

- Factors that could change the distribution of benefits include the participant’s distance to the evaluation site, primary language, computer access, computer and health literacy skills, race and ethnicity, and income level.

Trauma-Informed Evaluation

- Asking someone about trauma is asking that person to recall potentially difficult events from their past.

- If absolutely necessary for the evaluation to ask questions about potentially traumatic events, incorporate a trauma-informed approach to collect data in a sensitive way.

- Amherst H. Wilder Foundation Fact Sheet on Trauma-Informed Evaluation

- More information on Trauma-Informed Evaluation

- The Institutional Review Board (IRB) is an administrative body established to protect the rights and welfare of human research subjects recruited to participate in research activities.

- The IRB is charged with the responsibility of reviewing all research, prior to its initiation (whether funded or not), involving human participants.

- The IRB is concerned with protecting the welfare, rights, and privacy of human subjects.

- The IRB has authority to approve, disapprove, monitor, and require modifications in all research activities that fall within its jurisdiction as specified by both the federal regulations and institutional policy.

- Click here for more information on the IRB, including contact information for your local IRB

- Depending on the nature of the evaluation, the IRB may exempt a program from approval, but an initial review by the Board is recommended for all programs working with minors.

Step 5

Step 5: Collect Data, Analyze, and Act

The fifth step in designing your evaluation is to implement the evaluation - Collect Data, Analyze, and Act! As part of an evaluation, you should:

- Collect data before, during, and after your program has completed

- Complete analysis after the completion of data collection

- Act upon your analysis by sharing evaluation results with stakeholders, and if needed, adapt future iterations of your program to address gaps identified through the evaluation

- Ensure the privacy and confidentiality of all participants.

- Select a sampling strategy that will allow for reporting on program outcomes.

- Consider whether quantitative and/or qualitative data collection methods are appropriate for reporting on program outcomes.

Privacy/Confidentiality

- Privacy and confidentiality of collected data should be ensured.

- Seek consent from all evaluation participants.

- Consider how you will secure data collected to protect sensitive information.

- Data stored electronically should, at minimum, be password-protected.

- If you are collecting information on illegal behaviors, such as recreational drug use, a confidentiality certificate can be used to protect sensitive information gathered from participants.

- This certificate prohibits the release of identifiable, sensitive information, except in specific cases when consent is obtained from the participant. For more information, visit the NIH website on certificates of confidentiality.

Sampling Strategies

- Sampling is the way that individuals are selected from a larger group to complete data collection activities.

- Generally, sampling strategies can be divided into non-probability sampling and probability (random) sampling.

- Sample size calculators are useful for determining the number of data points that are needed to detect a statistically significant difference.

- More information on sampling strategies

Choosing a Sampling Strategy

- Is a sample needed or is your program population small enough that it is feasible to survey everyone?

- If you are not trying to generalize your findings to the whole community, this may be easier to achieve.

- If you want to generalize findings to the whole community, then you need to collect information from the whole community, not just program participants. In this case, consider collecting a sample.

- If a sample will be selected, will it be necessary to conduct probability (statistical) sampling?

- In rural health settings, it may not be possible to obtain a sampling frame, a list of all individuals or households from which a sample will be selected.

- In addition, if you do not intend to generalize to the full participant population (i.e. you won't make conclusions about all participants based on data from a sample of participants), probability sampling is not necessary. Non-probability samples may provide enough information and are less cumbersome to select.

Non-probability Sampling

| Sampling strategy | Example use in Rural Health programming |

|---|---|

| Convenience sample | Select a number of individuals visiting the library where the program is being conducted until the sample size is met. |

| Quota sample | An evaluator learns that approximately 30% of the population in the rural area lives within 5 miles of the library, and 70% lives farther away. With a sample size of 100, the evaluator asks 30 participants who live within 5 miles of the library and 70 who live farther away from to complete a survey. |

| Volunteer or self-selected sample | Ask all individuals who attended a community outreach event to complete a survey, if they feel comfortable. |

Probability Sampling

| Sampling strategy | Example use in Rural Health programming |

|---|---|

| Simple random sample | An evaluator wants to say that the program improves an outcome in an entire community. After calculating a sample size, a random number table is used to select households to survey. |

| Systematic random sample | From a list of all visitors to an information corner, an evaluator interviews every 5th visitor. |

| Stratified sample | From a list of all program participants, groups are assigned groups according to a common trait – sex, socioeconomic status, etc. From there, a simple random sample group from each strata (group) would be selected to participate in the study. |

| Cluster sample | An evaluator wants to say that the program improves an outcome in an entire community. The community is divided into clusters of roughly the same size based on geographic area. The same number of households in each cluster are randomly selected, and complete a survey. |

Data Collection Methods

| Data collection method | Example use in Rural Health programming |

|---|---|

| Questionnaire/ Survey | Questionnaires or surveys are a good solution for collecting data from a large group of participants, say from a whole community, or from many different stakeholders, like seminar participants, librarians, and volunteers. |

| Knowledge assessment | A health information program in a rural area that wants to understand if knowledge of promoted health information has changed over time. |

| Focus Group | Focus groups are a good way of collecting data from any stakeholder group (librarians, community members, etc.) that have shared a common role within the program. They provide more depth and context to survey findings. |

| Observation | Observations can assist evaluators in understanding how effective their program is working overtime. A program that expects interaction with passively delivered information, such as posters, bulletin boards, or information corners, can observe how participants interact with the information. |

| Interview | Interviews can serve to solicit specific information from individual stakeholders. A program manager may be interviewed to help uncover difficulties with program implementation. |

Quantitative Analysis

- Quantitative data are information gathered in numeric form.

- Analysis of quantitative data requires statistical methods.

- Results are typically summarized in graphs, tables, or charts.

- More information on quantitative analysis.

Qualitative Analysis

- Qualitative data are information gathered in non-numeric form, usually in text or narrative form.

- Analysis of qualitative data relies heavily on interpretation.

- Qualitative data analysis can often answer the 'why' or 'how' of evaluation questions.

- More information on qualitative analysis.

- Share information gathered in your evaluation with stakeholders to ensure they understand your program successes and challenges.

- Align stakeholders around the program and allow for planning for future iterations or versions of the program.

- Evaluations can be summarized as evaluation reports, Power Point Presentations, dashboards, static infographics, and/or 2-page briefs depending on the needs of stakeholders.

Meeting Rural Health Stakeholder Needs

- Creation and review of findings with community members and stakeholders can help ensure that information is presented in a respectful way.

- Responses to the outcomes found in the evaluation should include the direct involvement and decision making of multiple stakeholder groups and community members.

- Be open to other interpretations or responses to your evaluation findings.

- If a program is renewed for subsequent program cycles, then using the findings of the evaluation can improve how responsive the program is to the needs of program participants.

- The field of rural health has been gaining national attention as it has become clearer that systemic issues have led to significant health disparities. There may be opportunities to share your evaluation and methods with a growing network of rural health evaluation practitioners.

Example Evaluation Plan

Example Evaluation Plan

The Library of Medicine at Corretto University developed the Health Know-How program to improve health literacy and understanding in the rural town of Waltworth. The program seeks to improve health literacy by setting up information corners in the four libraries in the region and a monthly outreach clinic in one library to answer questions and promote online library health resources. The information corners include visual aids such as posters and fliers, as well as pamphlets and booklets that explain primary care, patient engagement in healthcare, health communication, and NNLM online resources available through the Library of Medicine. Health Know-How will utilize the Health Literacy Toolkit created by the National Network of Libraries of Medicine (NNLM) and the American library Association (ALA). The Library of Medicine will also order Easy-to-Read Health Books from the Institute for Healthcare Advancement on a variety of health topics to include the information corners.

Additionally, once a month an outreach clinic is held at the largest library in Waltworth. A health sciences librarian from the Library of Medicine will be present at the outreach clinic to answer questions, and to demonstrate online resources. The Library of Medicine at Corretto University is applying for a grant through NNLM and are in the process of creating their evaluation plan as part of their application.

SWOT Analysis

Prior to rolling out the program, Health Know-How staff met to discuss the team's internal strengths and weaknesses, as well as the strengths and barriers in the community to providing a quality program. In addition, they consulted with staff from a primary care health center to ensure multiple stakeholders' views were included. The results of that SWOT Analysis are in the diagram below.

Strengths

- Brings information from the Library of Medicine directly into the community

- Health literacy has been shown affect to overall health

- A wide variety of high-quality health literacy communications materials are available online

- Outreach clinics allow for reinforcement of health literacy topics

- Outreach clinics allow opportunities for demonstrations of Library of Medicine Resources

Opportunities

- Can build relationships between residents in Waltworth and the Library of Medicine at Corretto University

- Increases visibility of the Library of Medicine in Waltworth

- Could allow for promotion of primary care and telehealth options through Corretto University Health System to improve access

Weaknesses

- Only people who visit the grocery stores/pharmacies with the information corners will engage with the information

- Access to healthcare is still challenging, even if health literacy improves

- WiFi access can be inconsistent for outreach clinics

- Digital literacy and computer skills are needed to use Library of Medicine online resources

- Public has limited access to technology at home

Threats

- It may be difficult to determine when materials run out for restock of items

- Transportation between locations will require large amounts of resources (time, cost)

- Don’t know how important it is to translate materials into other languages

- Social media may have contradictory or confusing health messages to what is published through Health Know-How

The community assessment showed that a greater proportion of the population in Waltworth was over 65, as compared to the surrounding county. At home technology use was also lower in Waltworth than the surrounding county. These findings show the importance of the outreach clinic to help build technology skills. Additionally, it was found that 26% of the community speaks Spanish as a first language. Because of this, the program decided to add some Spanish language communications materials in the information corners.

The community assessment showed that a greater proportion of the population in Waltworth was over 65, as compared to the surrounding county. At home technology use was also lower in Waltworth than the surrounding county. These findings show the importance of the outreach clinic to help build technology skills. Additionally, it was found that 26% of the community speaks Spanish as a first language. Because of this, the program decided to add some Spanish language communications materials in the information corners.

Logic Model

Developing a program logic model assists program staff and other stakeholders in defining the goals of a project and develops a road map for getting to the goals. The logic model is also used during the evaluation process to measure progress toward the program goals.

The Health Know-How logic model is below.

Goal: Improve Health Literacy in Waltworth

Inputs

What we invest

- Materials for information corner and communication campaign

- Outreach clinic supplies (laptop, table, chairs, information, and marketing materials

- Library of Medicine staff for management and staffing outreach clinic

- Grant funding

Activities

What we do

- Establish information corners at all 4 libraries with visual aids and print materials

- Restock information corners every two weeks

- Complete communications campaign to promote Health Know-How

- Conduct outreach clinics once a month at the largest library

Outputs

What can be counted

- Waltworth community members who visit libraries view or engage with information corners

- Waltworth community members who attend outreach clinics

- Community members who visit outreach clinics are shown online resources

- Communication campaign reaches community-at-large with information on Health Know-How

Short-term Outcomes

Why we do it

- Increased knowledge of health topics

- Change in perceptions of health and individual role in healthcare

- Increased utilization of online resources

- More library patrons intend to practice healthy behaviors

Intermediate Outcomes

Why we do it

- Library patrons’ health literacy levels increase

Long-term Outcomes

Why we do it

- More library patrons participate more in the health system

- More library patrons practice healthy behaviors

Assumptions

- Everyone has access to the technology needed to improve health literacy

- Health literacy communication materials are engaging and interesting

- Improving health literacy will improve healthy behaviors

External Factors

- Rural setting means that there are large distances between residences and resources (-)

- Not all people will have insurance coverage or financing available to use medical or preventative services (-)

Measurable Indicators

Health Know-How reviewed the logic model with community leaders and decided upon a list of indicators that matched their goals. The table below shows some sample indicators.

| Outcome | Indicator |

|---|---|

| Short-term Outcome: Residents of Walworth improve their knowledge of health topics | Proportion of people surveyed who are able to correctly answer 80% of questions on health topics covered in communication materials in the information corners |

| Intermediate Outcome: Improve the health literacy levels library patrons | Proportion of participants who score as having ‘adequate’ health literacy using the Brief Health Literacy Screening Tool |

| Long-term Outcome: Library patrons practice healthy behaviors | Proportion of households surveyed who stated they completed five of the ten listed healthy behaviors in the past 2 weeks. |

Evaluation Design & Questions

For their evaluation, the Health Know-How team selected a Pre and Posttest with Follow-Up design in order to address all outcomes in their logic model.

After looking at different nearby geographic areas and subgroups within Waltworth, Health Know-How decided to use a pre-post evaluation design, because a reliable comparison group could not be found. An attempt was made to try to locate a reliable comparison group. The Health Know-How team considered surveying individuals who visit stores in Waltworth that don’t have an information corner. However, the typical person who shops at stores may be different than the typical person who visits libraries with information corners, and that may change the outcomes seen.

Process Questions

| Process Questions | Information to Collect | Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Were program activities accomplished? | Were communications materials printed? Were all four information corners set up as planned? Did all outreach clinics occur as planned? | Focused staff feedback sessions Observation of outreach clinics |

| Were the program components of quality? | Were materials engaging? Did Waltworth residents ever engage with the outreach clinics? Did participants find the outreach clinics helpful? | Observations of outreach clinics Observation of information corners Survey of outreach clinic participants |

| How well were program activities implemented? | Were all program components completed on time and on budget? | Focused staff feedback sessions Review of program records |

| Was the target audience reached? | What percentage of visitors to the library interact with the information corners? What percentage interact with the outreach clinics? | Count of library visitors Observation of information corners Attendance counts from outreach session |

| Did any external factors influence the program delivery, and if so, how? | Did digital literacy and computer skills change if participants were able to access online library health resources at home? Did the age of participants change their motivation or outcomes? Did distance from the libraries change how often participants engaged with health information? | Focus group with program participants Survey of outreach clinic participants |

Outcome Questions

| Outcome Questions | Information to Collect | Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Short-term outcomes | At the end of the program, did program participants’ knowledge of health topics change? At the end of the program, did program participants’ perceptions of health and their role in healthcare change? At the end of the program, did program participants’ utilize online library health resources at a different frequency than at the start? | Survey of individuals engaging with information corners Survey of outreach clinic participants |

| Intermediate outcomes | Did Health Know-How change the level of health literacy among library patrons? | Survey of people as they are leaving the library |

| Long-term outcomes | Do library patrons engage differently in the health system after the completion of Health Know-How? Do library patrons practice healthy behaviors more frequently after the end of Health Know-How? | Survey of people as they are leaving the library |