This pathway complements NNLM’s resources for LGBTQIA+ individuals by exploring evaluation considerations for programs that seek to improve health outcomes for members of this community.

People who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, non-binary, queer, questioning, intersex, or asexual/agender/aromantic (LGBTQIA+) are members of every community. These individuals often live in discriminatory environments, where their health needs may be inappropriately served or underserved.

Working on a project with a small award (less than $10,000)? Use the Small Awards Evaluation Toolkit and Evaluation Worksheets to assist you in determining key components for your evaluation!

When developing an evaluation, consider the context of your program. The context can change how your evaluation is designed and implemented since different settings and populations have different needs and abilities to participate in evaluations.

- Build trust through compassion and empathy. Members of the LGBTQIA+ community often face discrimination and a lack of cultural competence from service providers in healthcare settings. Examine your own assumptions to understand, empathize, and build trust with stakeholders to reduce harm in healthcare. Approach the evaluation process in a way that respects individual differences in order to create or adapt programming to meet all individuals' needs.

- Recommendations for conducting interviews with empathy from Stanford University's d.school

- There are many kinds of data relevant to the experiences of LGBTQIA+ community members, but only those relevant to the goals of the program should be collected. Depending on the program, these data points may include:

- Gender identity

- Gender expression

- Biological sex

- Sexual orientation

- Ensure confidentiality. Clear assurances of privacy of personal information, as well as nondiscrimination policies, should be made before data are collected.

- De-identify data. Data collected as part of a group sample should be de-identified so that single data points cannot be tied to individuals.

- Sexual orientation and gender identity are not synonymous and should not be treated as such.

- Sexual orientation - An inherent or immutable enduring emotional, romantic, or sexual attraction to other people

- Gender identity - One’s innermost concept of self as male, female, a blend of both, or neither – how individuals perceive themselves and what they call themselves; one’s gender identity can be the same or different from their sex assigned at birth

- Where it is appropriate and relevant to ensuring the health needs of all LGBTQIA+ program participants are met, the following background questions related to sexual orientation and gender identity are recommended.

- These questions have been adapted from those tested by the CDC through rural and urban health centers.

- NNLM grantees should determine if the same information is required in order for their program to equitably serve all participants.

| Sexual Orientation | |

|---|---|

| Do you identify as: |

|

| Gender Identity | |

| Do you identify as: |

|

| What sex is listed on your original birth certificate? |

|

- As an evaluator or program staff member, it is important to ask for and use each person’s pronouns. Be upfront with participants, asking how they would like to be addressed.

- The University of California San Francisco shares the following chart of commonly used pronouns and how they are used:

| Subject | Object | Possessive | Possessive Pronoun | Reflexive |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| He | Him | His | His | Himself |

| "He studied" | "I called him" | "His pencil" | "That is his" | "He trusts himself" |

| She | Her | Her | Hers | Herself |

| "She studied" | "I called her" | "Her pencil" | "That is hers" | "She trusts herself" |

| They | Them | Their | Theirs | Themself |

| "They studied" | "I called them" | "Their pencil" | "That is theirs" | "They trust themself" |

| Ze (or Zie) | Hir | Hir | Hirs | Hirself |

| "Ze studied" ("zee") | "I called hir" ("heer") | "Hir pencil" | "That is hirs" | "Ze trusts hirself" |

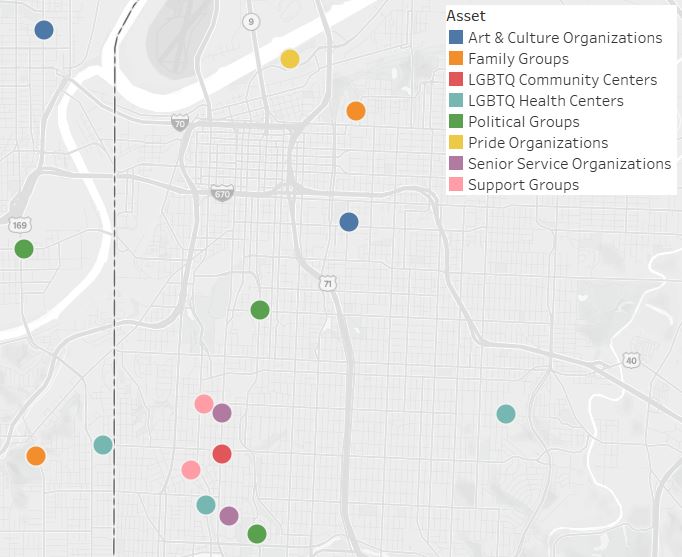

- Kimberlé Crenshaw's Intersectionality framework states that people experience multiple, overlapping, and cumulative forms of discrimination, such as racism, sexism, classism, and ableism.

- These different forms, or dimensions, of oppression intersect in complex ways, so that individuals who identify with multiple dimensions of oppression experience discrimination in different ways.

- This may justify the collection of additional data related to the needs of specific communities within your group of program participants.

- Intersectionality influences how questions related to LGBTQIA+ identification are framed. The Center for American Progress offers these examples:

- For communities where the primary language for a significant proportion of the population is not English, response options must be accurately translated into the local language(s).

- For communities where LGBTQIA+ terminology is not commonly used, those terms that are used frequently – like “two-spirit” in many Native American communities – should be used instead.

- In surveys, always include a fill-in option that allows each individual to describe themself and their background in their own words.

- More information on intersectionality

Disparities in programming areas

- The sample population should reflect the real population of the program. For example, the distribution of race/ethnicity, gender, etc. in the sample of survey respondents should be similar to the distribution of these characteristics in the full population of program participants.

- Consider barriers to participation. Where there are barriers to participation for certain groups, consider how these groups' needs can be met to ensure equitable participation in the evaluation.

Step 1: Do a Community Assessment

The first step in designing your evaluation is a community assessment. The community assessment phase is completed in three segments:

- Get organized

- Gather information

- Assemble, interpret, and act on your findings

- This phase includes outreach, background research, networking, reflecting on the evaluation and program goals, and formulating evaluation questions.

- Conduct a stakeholder analysis to identify individuals or groups who are particularly proactive or involved in the community. Find out why they are involved, what is going well in their community, and what they would like to see improved.

LGBTQIA+ Stakeholders

- Involvement of community stakeholders builds trust within the community and encourages buy-in and ownership of the program and evaluation process.

- A program is more likely to be responsive to the specific needs of the community and produce an evaluation that is relevant for all audiences if these stakeholders have a voice in the planning process.

- LGBTQIA+ community stakeholders may include donors, program staff, LGBTQIA+ program participants, family members and allies of LGBTQIA+ individuals, and partner organizations.

Stakeholder Analysis

- Consider identifying early adopters among LGBTQIA+ stakeholders. When creating a community assessment, consider the questions that could be asked to help identify these individuals and their role in the community.

- Use the Positive Deviance (PD) approach to identify these early adopters.

- Please note this process is time and labor intensive and requires a skilled facilitator comfortable with ambiguity and uncertainty. This process may not be feasible within the time constraints of the typical NNLM-funded project.

SWOT Analysis

- As part of the LGBTQIA+ stakeholder analysis, conduct a SWOT Analysis for the program to identify what you and your team already know.

- A SWOT analysis is typically used to assess an organization or program's internal strengths and weaknesses and the opportunities and threats to the organization or program in the external target community.

- More information on SWOT Analysis

- Example LGBTQIA+ SWOT Analysis

- This phase includes gathering data from different external and internal sources to inform the development of your program and evaluation plan.

- Consider how survey delivery may vary across stakeholders. Some stakeholders may have access to technology and the skills required to participate in an online survey (distributed via email or a shared link), while others may require phone or in-person surveys conducted by the project team or a paper and pencil survey used during an in-person event.

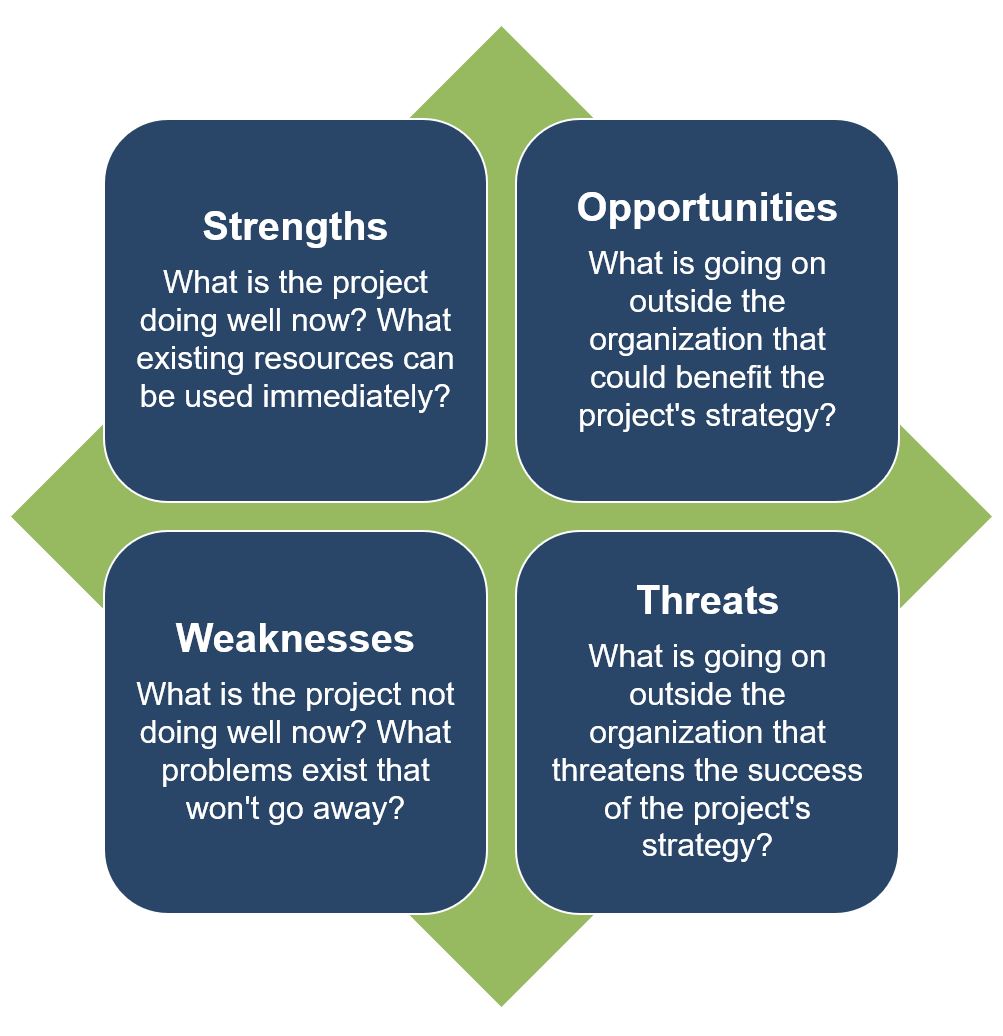

Participatory Asset Mapping

- Consider gathering information using a participatory asset mapping approach. This strategy engages stakeholders in canvassing their communities to document resources, needs, and opportunities. Outlining community assets from the perspective of LGBTQIA+ members provides a more comprehensive assessment of what resources are available to individuals and how best the new program can build upon these assets.

- Participants may consider the following data when outlining resources available in their local community. Ultimately, LGBTQIA+ individuals should determine the accuracy and applicability of any external data to the program and their community.

- Example LGBTQIA+ Participatory Asset Mapping exercise

Service Population Data

- Many secondary data sources used to support a needs assessment are not disaggregated by sexual orientation or gender identity.

- There may be situations where primary data collection is required to address the specific needs of the project’s audience. This can be done through focus groups or individual interviews, depending on the goals of the program.

- Focus group discussions:

- Focus group discussions are an interview technique used with small groups of participants who share similar characteristics or experiences

- No more than 10-12 individual participants are recommended.

- Questions about knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors related to the program design can be asked of the group to better understand what participants already know, believe, and do and where your program can fill the gaps.

- Individual interview:

- Interviews provide an opportunity to learn about an individual’s experience accessing health services as a member of the LGBTQIA+ community.

- While beneficial for data collection, individual interviews take a lot of time, so it is recommended these only be used to gather information from key individuals (another term for these in literature is ‘key informant interviews’).

- Focus group discussions:

- Example LGBTQIA+ program service population data collection process

Existing Data Sources

- Existing data, where available, can be a helpful resource for developing your evaluation plan.

- The following data sources CANNOT be used to report against program outcomes, but they may be helpful during a needs assessment or program design phase in understanding the context in which the program will be placed:

- The Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS) tracks health behaviors at the national, state, territorial, tribal, and local levels.

- Categories of health-related behaviors or classifications monitored include sexual behaviors and identity, alcohol and other drug use, unhealthy dietary behaviors, inadequate physical activity, and others.

- Programs planned to address student alcohol and drug use could use YRBSS data as the background for creating a needs assessment for the program or to highlight the need for their intervention as part of the program design.

- Outcomes related to a change in attitudes or behaviors at the end of the program would require a survey administered to the participants to measure that change.

- The National HIV Behavioral Surveillance (NHBS) tracks information on HIV-related risk behaviors, HIV testing, and use of HIV prevention services.

- Data are collected in rotating, annual cycles in three different populations at increased risk for HIV, including gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men; known as the MSM cycle.

- Data collected relate to behavioral risk factors for HIV (e.g. sexual behaviors, drug use), HIV testing behaviors, the receipt of prevention services, and use of prevention strategies (e.g. condoms, PrEP). In addition to these interview data, all NHBS participants are offered an HIV test.

- NHBS data are used to provide a behavioral context for trends seen in HIV surveillance data. They also describe populations at increased risk for HIV infection and thus provide an indication of the leading edge of the epidemic.

- Outcomes related to the impact of a specific intervention on LGBTQIA+ community members would need to be measured directly using a tool tailored to the outcomes and evaluation question(s).

- The Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS) tracks health behaviors at the national, state, territorial, tribal, and local levels.

This phase includes processing the information gathered into understandable takeaways that can be used for the program and the evaluation.

Gap Analysis

- To interpret and begin to act on results from your primary and/or secondary data sources, conduct a gap analysis.

- Like a needs assessment, a gap analysis seeks to identify the need(s) – or gap – that are not being addressed in a community.

- Conducting a gap analysis can justify the necessity of a specific program intervention or an adaptation to ensure all members of a population are receiving adequate and targeted services.

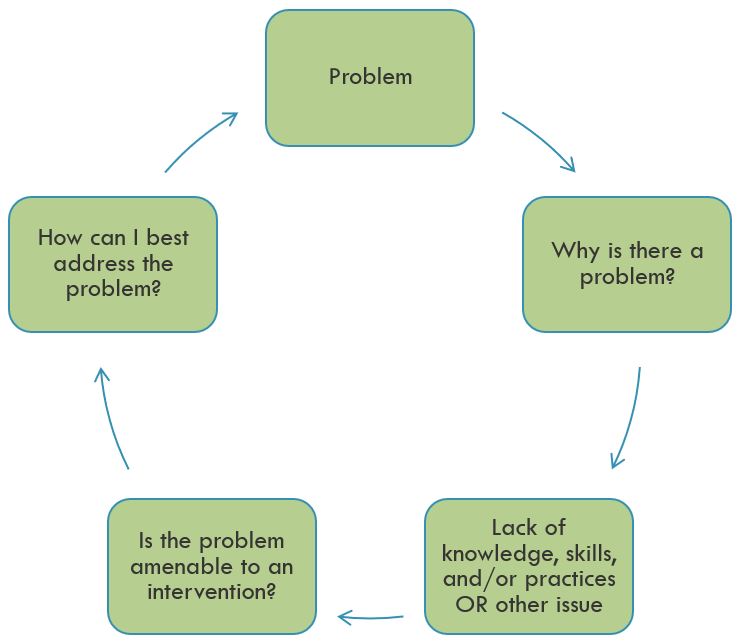

- By identifying the problem and the reason there is a problem, we can determine if and how our program can best address the problem.

- More information on gap analysis

- The following chart can be used to conduct the gap analysis.

- Example LGBTQIA+ program gap analysis

| Current State | Desired State | Identified Gap | Gap due to knowledge, skill, and/or practice | Methods used to identify professional practice gap |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| What is currently happening? | What should be happening? | Difference between what is and what should be. | Why do you think the current state exists? What is the underlying or root cause? | What evidence do you have to validate the gap exists? |

Step 2: Make a Logic Model

The second step in designing your evaluation is to make a logic model. The logic model is a helpful tool for planning a program, implementing a program, monitoring the progress of a program, and evaluating the success of a program.

- Consider how the program's logic model will assist in determining what is, or is not, working in the program's design to achieve the desired results.

- Be open to new and alternative patterns in your logic model. Have stakeholders and community members review your logic model, paying particular care to how change occurs across the logic model. Listen to voices who can say whether the strategies are beneficial, and whether strategies could be successful.

- More information on Logic Models

- Example LGBTQIA+ Logic Model

Tearless Logic Model

- To facilitate the creation of the logic model, community-based organizations can consider using the Tearless Logic Model process.

- The Tearless Logic Model uses a series of questions to assist non-evaluators in completing the components of the logic model. Questions used in the Tearless Logic Model

Knowledge, Attitudes, & Behaviors

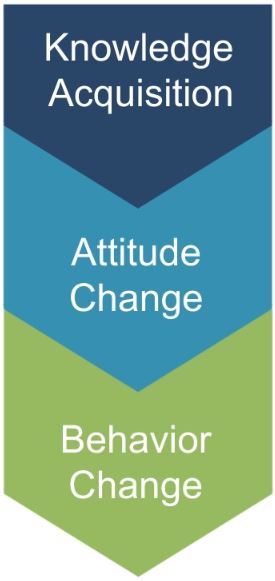

- Programming should consider improvement in the knowledge-attitude-behavior continuum among program participants as a measure of success. The process of influencing health behavior through information, followed by attitude changes and subsequent behavior change, should be documented in the logic model.

- Focusing on behavior change is more likely to require Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval.

- Knowledge Acquisition:

- What is the program trying to teach or show program participants?

- What understanding would a program participant gain over the course of the program? Often knowledge acquisition occurs as a short-term outcome of the program.

- Be sure to examine not only what is learned, but where, when, and how program participants will learn it.

- Attitude Change:

- What mindsets or beliefs is the program seeking to build or change? Be sure to consider cultural differences in attitudes in the community you are working with.

- Are there misconceptions about the topic, and does that belief change after program sessions/curriculum have been implemented?

- To what extent do participants agree with statements related to the new material presented?

- Behavior Change:

- After some time has passed from implementation of the program sessions/curriculum, are the actions of program participants different than what they presented before the program began?

- Are the new behaviors in alignment with the goals of the program?

- Note that most NNLM projects focus on the dissemination of health information/health education and often do not take place over a long enough period of time to observe behavior change.

- As such, examining/measuring behavior change may be out of the scope of the NNLM-funded project unless the projects runs for multiple cycles over an extended period of time.

Step 3: Develop Indicators for Your Logic Model

The third step in designing your evaluation is to select measurable indicators for outcomes in your logic model.

Measurable Indicators

- Consider whether your outcomes are short-term, intermediate, or long-term

- Most NNLM projects are of short duration and should focus only on short-term or intermediate outcomes.

- It may be necessary to use more than one indicator to cover all elements of a single outcome.

- Indicators examining changes in programs working with members of the LGBTQIA+ community should consider how being a member of the community might result in different outcomes than if the person was not a member of the LGBTQIA+ community.

- Do members feel they can live an open and authentic life in their broader community?

- Has this group traditionally experienced disparities in the health system because their specific needs were not addressed (or even considered)?

- Do they feel safe and included within the health space so that they are willing to seek out additional health information or assistance when needed?

- Understanding barriers to participation or engagement can help you as program staff determine what indicators are feasible for data collection purposes.

- How to develop measurable indicators

- Example LGBTQIA+ Measurable Indicators

Demographic Data

- Collect data on demographics as part of your survey process. It is important to understand your participants' backgrounds and how that may affect their engagement with your program.

- During analysis, compare differences in backgrounds against outcome results. If there are gaps identified in reaching certain populations, consider adjustments to program implementation to serve all participants equitably.

- More information on collecting demographic data

Step 4: Create an Evaluation Plan

The fourth step in designing your evaluation is to create the evaluation plan. This includes:

- Defining evaluation questions

- Developing the evaluation design

- Conducting an ethical review

- Evaluation questions help define what to measure and provide clarity and direction to the project.

- Process questions relate to the implementation of the program and ask questions about the input, activities, and outputs columns of the logic model.

- Outcome questions relate to the effects of the program and relate to the short, intermediate, and long-term columns of the logic model.

- Evaluation design influences the validity of the results.

- Most NNLM grant projects will use a non-experimental or quasi-experimental design.

- Quasi-experimental evaluations include surveys of a comparison group - individuals not participating in the program but with similar characteristics to the participants - to isolate the impact of the program from other external factors that may change attitudes or behaviors.

- Non-experimental evaluations only survey program participants.

- If comparison groups are part of your quasi-experimental design, use a 'do no harm' approach that makes the program available to those in the comparison group after the evaluation period has ended.

- More information on Evaluation Design

Ethical Considerations

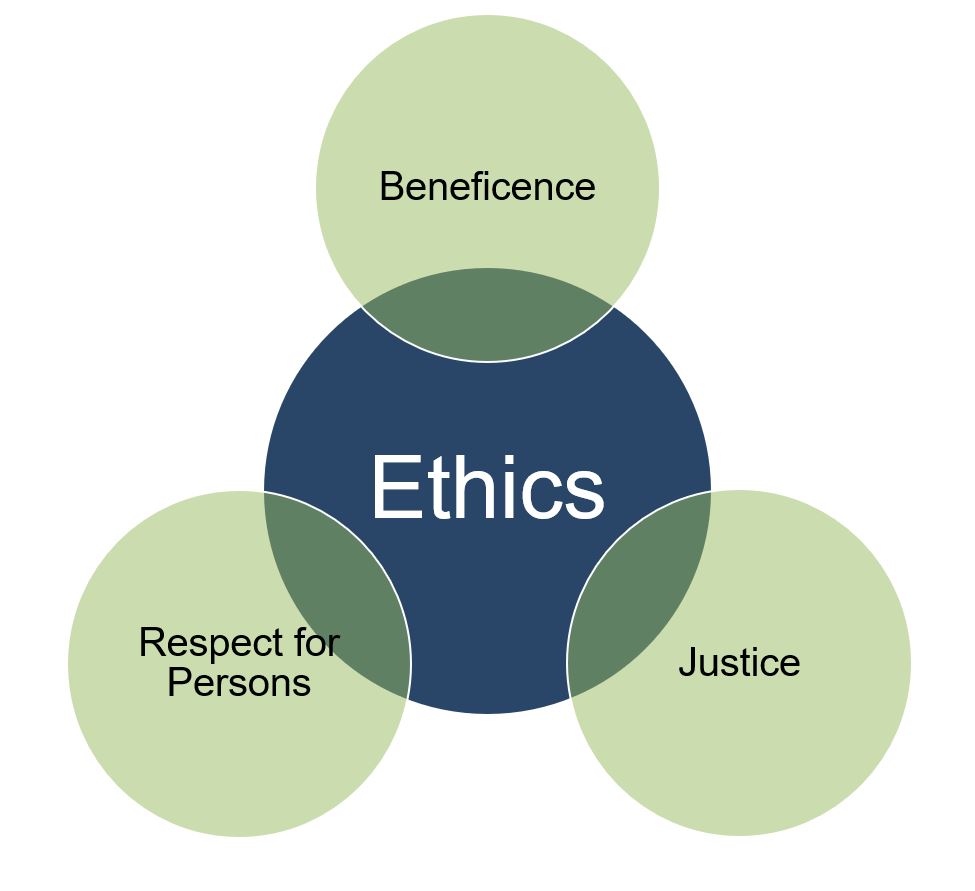

Consider the Belmont Report principles to examine LGBTQIA+ population ethical considerations:

- Respect for Persons:

- Individual determination - that is the ability of an individual to make decisions about themselves- is important for evaluation.

- When evaluating programs with participants who are part of the LGBTQIA+ community, consider the effect simply participating in the evaluation may have on them.

- If someone feels participating in the evaluation requires them to express their identity in a way they are not comfortable sharing publicly or requires a level of personal information sharing they are simply not comfortable with, they may feel coerced to respond a certain way they may not otherwise agree with.

- When involving community members in the evaluation or obtaining consent for your evaluation, try to minimize the pressures individuals feel to act or respond a certain way.

- Allowing anonymous decision making and feedback, when possible, can reduce the pressures individuals feel to behave a certain way.

- Beneficence

- How will your evaluation balance the burden that participants take to complete the evaluation with the benefits of completing the evaluation?

- In the process of completing the evaluation, are you asking your participants to do things or participate in a way that makes them uncomfortable?

- Participatory evaluation can increase the benefits of the evaluation to the community.

- Including the perspectives of multiple stakeholders and community members allows for program participants to reduce the burdens of the evaluation, while increasing the benefits LGBTQIA+ community members feel.

- Justice

- Consider how your evaluation would exacerbate or improve the recognition of health needs specific to the LGBTQIA+ community.

- In communities where members of the LGBTQIA+ community feel they must keep their identity or orientation hidden so as to avoid discrimination, justice can be difficult to assess when discrimination is entrenched in the systems, structures, and norms of the society.

- Try to assess how the program affects different groups of people within your program.

- Consider that there may be groups who are less visible in the LGBTQIA+ community than others, including those who do not speak English, older adults, individuals with disabilities, low-income households, and medically vulnerable people.

Trauma-Informed Evaluation

- Asking someone about trauma is asking that person to recall potentially difficult events from their past.

- If absolutely necessary for the evaluation to ask questions about potentially traumatic events, incorporate a trauma-informed approach to collect data in a sensitive way.

- Amherst H. Wilder Foundation Fact Sheet on Trauma-Informed Evaluation

- More information on Trauma-Informed Evaluation

- It may be beneficial to complete a human-subjects research training, online or in person, if you are working with vulnerable populations or have more questions about ethical review or the ethical review process.

- The Institutional Review Board (IRB) is an administrative body established to protect the rights and welfare of human research subjects recruited to participate in research activities.

- The IRB is charged with the responsibility of reviewing all research, prior to its initiation (whether funded or not), involving human participants.

- The IRB is concerned with protecting the welfare, rights, and privacy of human subjects.

- The IRB has authority to approve, disapprove, monitor, and require modifications in all research activities that fall within its jurisdiction as specified by both the federal regulations and institutional policy.

- Click here for more information on the IRB, including contact information for your local IRB

- Depending on the nature of the evaluation, the IRB may exempt a program from approval, but an initial review by the Board is recommended for all programs.

- If you are working in a community or district with its own public health department, first check with the local public health department before consulting the state-level public health department.

- If using health records from health care facilities, review patient privacy laws in your area.

- Most information from care facilities will be in electronic records, which have various safeguards to prevent unethical use.

- The use and transfer of protected health information (PHI) is regulated through multiple government policies, including the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA).

Step 5: Collect Data, Analyze, and Act

The fifth step in designing your evaluation is to implement the evaluation - Collect Data, Analyze, and Act! As part of an evaluation, you should:

- Collect data before, during, and after your program has completed

- Complete analysis after the completion of data collection

- Act upon your analysis by sharing evaluation results with stakeholders, and if needed, adapt future iterations of your program to address gaps identified through the evaluation

- Ensure the privacy and confidentiality of all participants. Informed consent from all participants is required.

- Select a sampling strategy that will allow for reporting on program outcomes.

- Consider whether quantitative and/or qualitative data collection methods are appropriate for reporting on program outcomes.

Privacy/Confidentiality

- Privacy and confidentiality of collected data should be ensured.

- In systems of inequality, confidentiality is especially important since the data collected could be used in a harmful manner to perpetuate stigmas against individuals or groups of people.

- It is the ethical responsibility of the evaluator to preserve confidentiality, and the steps taken to preserve confidentiality should be clearly communicated to participants. As an evaluator, ask yourself the following questions when preparing for data collection:

- Are the evaluators/program staff properly briefed on confidentiality and anonymity?

- What steps can I take to ensure confidentiality and anonymity?

- How might my evaluation topic affect confidentiality and anonymity?

- How might my evaluation methods affect confidentiality and anonymity?

- What other factors might affect my ability to preserve confidentiality and anonymity?

- How do I intend to store the data? (It cannot be accessed by anyone outside the evaluation)

- How can I ensure confidentiality and anonymity in funded research

- Consider how you will secure data collected to protect sensitive information.

- Data stored electronically should, at minimum, be password-protected.

Sampling Strategies

- Sampling is the way that individuals are selected from a larger group to complete data collection activities.

- Generally, sampling strategies can be divided into non-probability sampling and probability (random) sampling.

- Sample size calculators are useful for determining the number of data points that are needed to detect a statistically significant difference.

- More information on sampling strategies

Choosing a Sampling Strategy

- Is a sample needed or is your program population small enough that it is feasible to survey everyone?

- For a program with 20 participants, for example, the total number of participants is small enough that it is likely more work to create a truly representative sample.

- However, if a program is operating in all libraries in the region, collecting data from a sample of participants will likely save time and money and produce similar results as surveying everyone.

- If a sample will be selected, will it be necessary to conduct probability (statistical) sampling?

- If it is not feasible to compile a list of sampling units, random selection (required for statistical samples) will not be possible.

- For example, you would need a full roster of participants in all libraries to create a truly random sample. If program confidentiality rules prevent this, a random selection of participants would not be possible.

- In addition, if you do not intend to generalize to the full participant population (i.e. you won't make conclusions about all participants based on data from a sample of participants), probability sampling is not necessary. Non-probability samples may provide enough information and are less cumbersome to select.

- If it is not feasible to compile a list of sampling units, random selection (required for statistical samples) will not be possible.

Non-probability Sampling

| Sampling strategy | Example use in LGBTQIA+ programming |

|---|---|

| Convenience sample | Select individuals visiting the library to access a specific program. |

| Quota sample | If you want to survey users of a specific program and your needs assessment shows 20% of LGBTQIA+ community members are nonbinary, you would try to ensure 20% of your survey respondents were nonbinary. |

| Volunteer or self-selected sample | Participants who are willing to visit the library to access the specific program are the survey participants. |

Probability Sampling

| Sampling strategy | Example use in LGBTQIA+ programming |

|---|---|

| Simple random sample | At the library providing a specific program, library staff can use a random numbers table to determine which of the pre- and post- knowledge tests will be used as part of the evaluation once survey results have been collected from all participants. |

| Systematic random sample | At the library providing a specific program, library staff may choose to interview every third person who arrives at the library. |

| Stratified sample | Begin by assigning participants to groups according to a common trait – sex, socioeconomic status, etc. From there, a random group of participants from each strata (group) would be selected to participate in the study. |

Data Collection Methods

| Data collection method | Example use in LGBTQIA+ programming |

|---|---|

| Questionnaire/ Survey | Questionnaires or surveys are a good solution for collecting data from a large group of participants or from many different stakeholders, like LGBTQIA+ seniors, health organization participants, library staff, etc. |

| Knowledge assessment | Knowledge assessments are strongly recommended for any program that is centered on specific curriculum for achieving program goals. |

| Focus Group | Focus groups are a good way of collecting data from any stakeholder group (LGBTQIA+ community members, health practitioners, program staff, etc.) that have shared a common role within the program. While knowledge assessments are critical for understanding if the program content has been understood, focus groups can be beneficial in helping program staff understand if the way in which the program has been implemented was effective, efficient, and ultimately sustainable. |

| Observation | Observations can assist evaluators in understanding how effective their program is working over time. Facilitating the curriculum over many sessions will show if and how it is being taught with fidelity, while the attitude and behavior changes of participants over time likely reflect the level of quality of the curriculum and its use through the program. |

| Interview | Interviews can serve to solicit specific information from individual stakeholders. |

Quantitative Analysis

- Quantitative data are information gathered in numeric form.

- Analysis of quantitative data requires statistical methods.

- Results are typically summarized in graphs, tables, or charts.

- More information on quantitative analysis.

Qualitative Analysis

- Qualitative data are information gathered in non-numeric form, usually in text or narrative form.

- Analysis of qualitative data relies heavily on interpretation.

- Qualitative data analysis can often answer the 'why' or 'how' of evaluation questions.

- More information on qualitative analysis.

- Share information gathered in your evaluation with stakeholders to ensure they understand your program successes and challenges.

- Align stakeholders around the program and allow for planning for future iterations or versions of the program.

- Evaluations can be summarized as evaluation reports, Power Point Presentations, dashboards, static infographics, and/or 2-page briefs depending on the needs of stakeholders.

Meeting LGBTQIA+ Stakeholder Needs

- Evaluations that are working to reduce disparities within the LGBTQIA+ community need to be transparent and fully detail the evaluation process from start to finish.

- Evaluations can raise awareness, mobilize supporters, and start the difficult process of social change.

- However, evaluations can also reinforce negative stereotypes and further divide or blame groups for negative outcomes.

- All outcomes found should be placed within the larger context, including the influence of systemic injustices and systemic issues like government policies, resource allocation, and community prejudices against members of the LGBTQIA+ community.

- Providing concrete, well-examined data to understand the outcomes in the context of the society in which they take place can move forward positive change.

- Review of findings with community members and stakeholders can help ensure that information is presented in a respectful way.

- Determining responses to the outcomes found in the evaluation should include the direct involvement and decision making of multiple stakeholder groups and community members.

- Be open to other interpretations or responses to your evaluation findings. If a program is renewed for subsequent program cycles, then using the findings of the evaluation can improve how responsive the program is to the needs of program participants.

- Disseminating information from the evaluation back to the community that you worked with can help ensure accountability and clarify subsequent actions.

- It is a sign of respect to include the community that you worked with, and an all too often forgotten piece of evaluation.

- One method of sharing findings is to hold a seminar with community members where you go over findings and hand out paper copies of the evaluation report to community members.

Example Evaluation Plan

The Community Library Health Workshop Series is designed to address the needs of seniors (55+) in the LGBTQIA+ community. A partnership between the county’s public health department and community library, the Health Workshop Series promotes in-person and virtual resources to support a continuum of healthcare. The local library coordinates a quarterly workshop series on health needs facilitated by health professionals and hosted at the library.

In addition to serving the local community to meet immediate health needs, the Community Library Health Workshop Series also boosts library staff’s confidence in meeting community members’ needs in accessing health information. Staff will complete the NNLM course, “Beyond the Binary: Health Resources for Sexual and Gender Minorities,” as part of their training to organize the Community Library Health Workshop Series.

The goal of the Community Library Health Workshop Series is to increase knowledge, and if needed to promote a healthy lifestyle, change behaviors as it relates to the specific health needs of seniors in the LGBTQIA+ community. The Health Workshop Series offers seniors access to health-related information, both through in-person presentations and group discussions and via virtual health resources available through the library.

SWOT Analysis

Prior to rolling out the workshop series, library staff met to discuss the team's internal strengths and weaknesses, as well as the strengths and barriers in the community to providing a quality program to the LGBTQIA+ senior community. In addition, they consulted with staff from local health organizations to ensure multiple stakeholders' views were included. The results of that SWOT Analysis are in the diagram below.

Strengths

- Partnerships between library and local health organizations already established

- Health curriculum ready for use

- Examples of effective workshop series at other libraries in Network

- Effective and engaged community public health system

- Financial resources available to support workshop series

Opportunities

- Educate using library resources

- Build partnerships between health organizations and library staff

- Build relationships between library staff and seniors in the LGBTQIA+ community

- Library seen as hub for health-related information

- Introduction of new, relevant health information to participants

- Educate library staff on assisting public in accessing health information

Weaknesses

- Seniors may choose not to participate in the workshop series

- Language barriers, lack of interpreters, or translated health material

- Limited transportation options to the library

- Lack of adequate financial resources to expand the program beyond the first year

- Limited library hours for access to health information

Threats

- Budget cuts, lack of financial resources

- Time constraints for engaging with seniors

- Seniors may be overwhelmed with new health information

- Seniors may have specific learning needs that limit participation (vision/hearing difficulties, digital literacy, etc.)

- Personal bias, attitudes

Participatory Asset Mapping

As part of the Gathering Information stage of Step 1, staff met with LGBTQIA+ members and local health organizations to map resources in their community. Through this process, staff discovered there are many organizations already doing great work with LGBTQIA+ members, many of whom they can now work in partnership with to provide holistic services to LGBTQIA+ seniors.

Service Population Data

The Community Library Health Workshop Series staff struggled to find secondary data that was disaggregated by sexual orientation or gender identity in the community where the program takes place, so they decided to collect primary data from community members to support their needs assessment. As part of a focus group discussion with LGBTQIA+ senior community members, as well as through individual interviews with LGBTQIA+ community organizers and staff at local health organizations, the staff will seek to answer the following questions:

- What is it about your community that makes it easier to be LGBTQIA+?

- Where do you currently access health information specific to your needs as a senior and member of the LGBTQIA+ community?

- What gaps in these services currently exist?

- What challenges have you experienced in the past accessing health information or services specific to your needs as a senior and member of the LGBTQIA+ community?

- What does or would make it easier to address these challenges of accessing health information specific to your needs?

Gap Analysis

Upon completion of the SWOT analysis, participatory asset mapping, and collection of service population data, Community Library Health Workshop Series staff used a gap analysis to identify the needs - or gaps - that are not currently being addressed in the LGBTQIA+ senior community.

| Current State | Desired State | Identified Gap | Gap due to knowledge, skill, and/or practice | Methods used to identify professional practice gap |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 60% of identified seniors in the LGBTQIA+ community report receiving the health information they need | 100% of identified seniors in the LGBTQIA+ community receive the health information they need | 40% of identified seniors in the LGBTQIA+ community are not receiving the health information they need | Knowledge – Unaware of resources available to them through health organizations and the local library | Survey among seniors identified consistent gaps in accessing health information from these sources |

Logic Model

Developing a program logic model assists program staff and other stakeholders in defining the goals of a project and develops a road map for getting to the goals. The logic model is also used during the evaluation process to measure progress toward the program goals.

The Community Library Health Workshop Series logic model is below.

Goal: Improve understanding of health issues specific to members of the senior LGBTQIA+ community

Inputs

What we invest

- Library staff member time for training on new material & liaising with community health partners

- Space/ resources for quarterly meetings

- Supplies for supplemental print health resources (booklets, pamphlets) and community advertising of Workshop Series

Activities

What we do

- Provide access to health workshops for LGBTQIA+ seniors through the library

- Provide supplemental print health resources for seniors to take home and reinforce learning

- Train library staff on sharing health resources with LGBTQIA+ community

Outputs

What can be counted

- LGBTQIA+ seniors registered to attend Workshop Series attend on a regular basis

- Seniors take home supplemental health resources from the library at the completion of sessions

- Librarians receive NNLM Health Resources training

Short-term Outcomes

Why we do it

- Seniors learn about health topics specific to them and learn of resources available to them through the community

- Seniors report gaining new knowledge after each session

- LGBTQIA+ seniors access other health resources available through their local library

- Library staff improve their knowledge of health resources available through the library that benefit LGBTQIA+ community members

Intermediate Outcomes

Why we do it

- Seniors change attitudes related to health matters relevant to them taught through library-based health workshops

- Library staff are seen by seniors as a resource for additional health information

Long-term Outcomes

Why we do it

- Seniors seek out assistance related to their health needs

- Seniors report changed behaviors related to health topics discussed as part of the workshop series

- Providing health assistance to seniors is part of at least one library staff member's official job description

Assumptions

- Local public health experts are open to partnering with the library for the duration of the program

- Seniors can physically visit the library

- Seniors find the material interesting and complete the workshop series

- Library staff members are dedicated to improving their practice

External Factors

- Library is only accessible via public transportation for some seniors (-)

- Library and public health experts are highly motivated to partner on this project (+)

Measurable Indicators

After developing the program logic model, Community Library Health Workshop Series staff create measurable indicators for all outcomes in the logic model. An example of a short-term, intermediate, and long-term outcome with corresponding measurable indicator is included in the chart below.

| Outcome | Indicator |

|---|---|

| Short-term Outcome: Seniors learn about health topics specific to them and learn of resources available to them through the community | Proportion of seniors participating in the workshop series who score 80% or better on post-course surveys |

| Intermediate Outcome: Seniors change attitudes related to health matters relevant to them taught through library-based health workshops | Proportion of seniors who report a change in attitudes toward health matters at the completion of the workshop series |

| Long-term Outcome: Seniors report changed behaviors related to health topics discussed as part of the workshop series | Proportion of seniors who report an increase in healthy behaviors 6 months after completing the workshop series |

Evaluation Design & Questions

For their evaluation, Community Library Health Workshop Series staff selected a Pre and Posttest with Follow-Up design in order to address all outcomes in their logic model.

As part of their evaluation design, the Community Library Health Workshop Series staff have the option of choosing process or outcome evaluation questions. For NNLM grantees, there is NO requirement to do both. Instead, it is important to select an evaluation design and questions that will enable staff to collect the data they need to accurately report on the outcomes in their logic model. Example process and outcome evaluation questions for the Community Library Health Workshop Series are below.

Process Questions

| Process Questions | Information to Collect | Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Were program activities accomplished? | Was the Community Library Health Workshop Series delivered by the library as planned? | Focused staff feedback sessions Observation of activities |

| Were the program components of quality? | Did seniors report learning something new and/or connecting with a new resource during the Health Workshop Series? | Pre- and post-tests for workshop sessions Feedback forms from participants |

| How well were program activities implemented? | Were library staff able to recruit local health experts so that the Health Workshop Series could be done quarterly? | Focused staff feedback sessions Observation of activities |

| Was the target audience reached? | Did the number of seniors who attended the Health Workshop Series meet or exceed the target number outlined in the evaluation plan? | Attendance counts |

| Did any external factors influence the program delivery, and if so, how? | How did the location of seniors’ homes impact their ability to access the Health Workshop Series? | Feedback forms with participants |

Outcome Questions

| Outcome Questions | Information to Collect | Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Short-term outcomes | Did the health partners deliver the Workshop Series curriculum as planned? Did library staff members’ understanding of library health resources improve after attending the NNLM course? | Pre- and post-tests for workshop sessions Feedback forms from participants Focused staff feedback sessions |

| Intermediate outcomes | Did the Health Workshop Series change how many seniors engage with new health material and/or health professionals as needs dictate? Did the Health Workshop Series change seniors’ views on the library as a resource for health information? At the end of the Health Workshop Series, did seniors’ understanding of health issues affecting them change? | Feedback forms from participants |

| Long-term outcomes | Did the Health Workshop Series change behaviors among seniors in the LGBTQIA+ community that relate to health issues discussed during the Workshop Series? Did the Health Workshop Series change the role of library staff in providing health information to the senior LGBTQIA+ community? | Follow-up survey with participants and library staff |